Zappos’ best move, Gallup’s research suggests, might be to replace bad managers with great ones.

Online retailer Zappos recently announced that it will eliminate the traditional manager role throughout the company to flatten its hierarchical chain of command. Zappos is morphing into a “holacracy” — an organizational structure intended to eradicate bureaucracy and politics, promote self-governance, and distribute power more evenly. After the transition, employees won’t have formal job titles. And instead of forming conventional teams based on hierarchy and work function, they will move among 400 “circles” in which they can assume various roles based on project needs.

The concept isn’t new, but it hasn’t been widely implemented. Wisconsin-based Johnsonville Foods, Inc., for example, has used self-managed teams since the 1980s. And consulting firms such as WonderWorks now exist to support organizations through the transition.

With more than 3,000 employees, Zappos is the largest company yet to embrace the model — with a few of its own enhancements. For example, the company will allow its broadest circles to have some authority to dictate lower circles’ responsibilities, creating a limited pseudo-hierarchy. The company’s transition is expected to take at least a year and has already raised several questions in the business press. But one in particular that Zappos executives must consider is this: How will the company engage its employees with few, if any, traditional managers?

Managing for engagement

Gallup hasn’t studied the holacracy model specifically, but some of our research may shed light on the ultimate efficacy of Zappos’ decision. Gallup has measured the engagement of 27 million employees and in more than 2.5 million work units worldwide and has studied the manager’s role at hundreds of organizations. We find that in every workplace — no matter what country, industry, or market it operates in — managers are essential to building employee engagement.

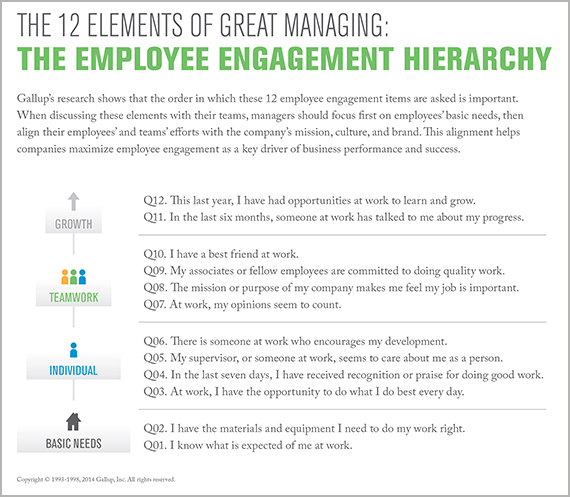

Gallup’s Q12 employee engagement survey consists of 12 actionable workplace elements proven to affect a company’s financial performance. Many of these items are driven by manager actions, such as setting clear expectations, positioning employees to use their strengths, and providing employees with regular recognition and praise. These 12 items sort high-performing teams from low-performing teams and can be locally owned, managed, and improved at the team level through manager-led efforts — provided the team has a direct manager.

The 12 engagement elements function like Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, with basic demands that must be fulfilled before employees can progress. For example, having a conversation about an employee’s progress makes little sense if he doesn’t know what is expected of him in his role.

Bridging from logistical concerns such as materials and equipment to professional development requires a manager’s support. A team manager has the proximity, authority, and expertise about his or her employees to implement change in their immediate environment. While employees are responsible for voicing their opinions, the best companies hold managers accountable for listening and responding to those opinions and creating positive change.

Because managers play such a key role in employee engagement, reducing or eliminating their role across a company could create an accountability vacuum that would wreak havoc on team-level engagement. Gallup has found that from workgroup to workgroup, employee engagement affects important business outcomes such as profitability, productivity, customer ratings, turnover, safety incidents, theft, absenteeism, and quality defects. Outcomes like these fluctuate widely in most companies, largely from the lack of consistency in how people are managed. And Gallup estimates thatmanagers are responsible for 70% of the variance in employee engagement from workgroup to workgroup. By taking managers out of the equation, this variance could go off the charts.

Gallup also reported in two large-scale studies in 2012 that only 30% of U.S. employees are engaged at work and just13% are engaged worldwide. What’s worse, over the past 12 years, these low numbers have barely budged, suggesting that the vast majority of employees worldwide are failing to reach their potential at work. If holacracy were to take off as a workplace trend, it’s tough to be optimistic about these low numbers improving, with no one focused on — or accountable for — meeting employees’ engagement needs.

The advantage of having great managers

Instead of reducing or eliminating traditional managers, Zappos’ best move, Gallup’s research suggests, might be to replace bad managers with great ones. Our studies show that great managers are rare, but they are worth the extra effort it takes to find them. Great managers can motivate employees to take action and can engage workers with a compelling mission and vision. They are assertive and can drive outcomes and overcome adversity and resistance. They create a culture of clear accountability. They build relationships that create trust, open dialogue, and full transparency. And they make decisions based on productivity, not politics. It’s possible that the problem Zappos perceives with bureaucracy and red tape is actually a lack of great manager talent in its organization.

Only about one in 10 people naturally have the traits to be a truly great manager — someone who naturally engages team members and customers, retains top performers, and sustains a culture of high productivity, contributing about 48% higher profit to his or her company than average managers do. Great managers create a substantial business advantage for their companies — one that Zappos and other like-minded businesses stand to lose if they drastically cut back on the ranks of their managers instead of focusing on hiring and developing the right people for the job.

As the largest organization to implement a holacracy, Zappos has a lot of questions to answer, and a volatile period of trial and error is likely yet to come. But as in any merger, restructuring, or other significant change, the company’s primary concern should be ensuring a smooth transition and the continued engagement of its workforce.

The irony here is that Zappos’ leaders may well be removing the main tool they have to ease that transition and maximize engagement — their team managers. Employees have widely varying needs related to morale, motivation, and clarity, and failing to meet those needs can lead to differing levels of effort and engagement at work. Nothing less than great managers can bring diverse groups of individuals together and focus them effectively on reaching higher levels of performance.